This year at Yale, two new literature classes will push the boundaries — cultural, linguistic, and geographic — of what we talk about when we talk about medieval literature. The aims of the classes are complementary but distinct: One will push against the strict definition of “English literature” in the Middle Ages, while the other will challenge the notion of borders between both the societies and the literary genres of the medieval world.

The first, “Multicultural Middle Ages,” a fall-term lecture course taught by Ardis Butterfield, the Marie Borroff Professor of English and professor of French and of music, is described in the Yale course catalog as an “introduction to medieval English literature and culture in its European and Mediterranean context, before it became monolingual, canonical, or author-bound.” The second, “Medieval World Literature, Genres and Geographies,” a spring-term seminar taught by Samuel Hodgkin, assistant professor of comparative literature specializing in Persian and Turkic literatures, is a “comparative survey of classic texts from around the medieval world.” Butterfield’s class will meet Mondays and Wednesdays 9:25-10:15 a.m., starting on Aug. 28.

Medieval misconceptions debunked

In “Multicultural Middle Ages,” Butterfield says, she wants to rescue the medieval era from popular contemporary misconceptions — both neutral and negative. For non-experts, she explains, the term “medieval” at best conjures images of “peasants digging in a field” or connotes cruelty, as illustrated by the Merriam-Webster definition she includes on the course syllabus. At worst, in recent years the symbols and events of the medieval period have been co-opted and distorted by white supremacist groups, she says.

“Charlottesville shocked a lot of us who teach the medieval period, seeing white supremacists using things like medieval runes and these images of warfare and weapons. It was the weaponizing of the Middle Ages for this particular political purpose,” says Butterfield, referring to the “Unite the Right” rally that marched in Charlottesville, VA two years ago this month.

Among other examples of misappropriation, she cites white supremacists’ continued use of the bogus Vinland map — a supposedly authentic, pre-Columbian world map discovered in the 1950s but debunked as a forgery by the 1970s — to prop up a racist origin story for the Americas — the claim that the Norse explorers found America before Columbus did. (The Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale holds the Vinland Map in its collections; Butterfield will take her students to see the map in person as part of the course.)

There’s a sense of political and social urgency about not allowing certain groups in society to take over periods of history and misappropriate them.

Ardis Butterfield

“There’s a sense of political and social urgency about not allowing certain groups in society to take over periods of history and misappropriate them,” she says. “If we don’t counter that kind of view in a place like Yale, then what are we doing?”

Actually, says Butterfield, we should be looking instead to the medieval period as this very liberating, flexible, fluid space where we can rethink definitions. “What does ‘English’ literature mean? If it doesn’t mean what we think it does in this period, does it mean what we think it means in later periods?”

In medieval England, the definition of “English” is anything but simple and fixed, she says. From roughly 1066 through the beginning of the 15th century, the dominant written language in intellectual and poetic culture was actually not English but Latin, with French coming second, explains Butterfield. Children were not taught to read and write English, only Latin. Geoffrey Chaucer — the most famous of all “Middle English” writers and a staple of most English department curricula — had a French wife; read French, Latin, and Italian; and spent significant time elsewhere in Europe, including France, Spain, and Italy. Butterfield notes that 1066 was also the year that William the Conqueror led the Norman invasion of England, which brought even more French influence across the Channel. In the Middle English language, many words were actually French.

Many medieval English literature classes stick to English-language original texts and authors, such as Chaucer, the Gawain poet, John Gower, and William Langland. “This seems obvious, but in a funny way, it isn’t; because if you were looking at the period as a whole, a huge amount of writing that survives is in French and Latin,” says Butterfield. “Many of the English-language authors like Geoffrey Chaucer were reading and being influenced by what their contemporaries wrote in other languages.”

Butterfield says she was delighted to turn her own “passive knowledge” of this fact into an active approach when she first started her graduate research. “I think everybody gets routinely taught that Chaucer read things in French, but actively making it part of your knowledge means reading those texts for yourself,” she explains, as students who take her course will do.

Chaucer’s “Canterbury Tales” remains on the syllabus of “Multicultural Middle Ages” (“I mean Chaucer is so brilliant, I have to teach Chaucer,” says Butterfield) but the class will also study Dante’s “Inferno” (Italian), “The Book of Margery Kempe” (English), “The Romance of the Rose” (French), “Mandeville’s Travels” (English and French), and selections of Hispano-Arabic poetry, among others. (All texts will be available in English translations.)

Page from the illuminated (illustrated) manuscript of “Mandeville’s Travels” depicting Sir John Mandeville witnessing the griffins of Bacharia. Circa 15th century. Held by the British Library.

In recent years, the Department of English has adjusted its required curriculum to make course offerings more diverse and flexible. Butterfield sees offering new, and unconventional, courses like “Multicultural Middle Ages” as a key part of the ongoing effort to promote greater inclusivity in the way Yale teaches and studies English literature.

“It’s quite tempting to think that we can be diverse only in the modern period, but we can be inclusive about the Middle Ages too. Not only should we open up our eyes to different perspectives in a much earlier period but also, weirdly enough, this earlier period also can be very transforming for the way in which we think of things now.”

Butterfield says there are two things she would love students to take away from the class. First, she wants them to come away with a “love and respect” for the medieval period and a general fascination about the past. But also, she would “love it to be a kind of route towards people questioning our attitudes about the past, questioning the present as a result of thinking about the past.”

A mobile, malleable Middle Ages

Where Butterfield is asking students to expanding their notion of what counts as “English” literature during the Middle Ages, Hodgkin will challenge his class to transgress all the boundaries placed around the medieval “verbal arts” of a single language, culture, or ruling state.

“It’s going to be an opportunity to find a way to think about the medieval world that’s not about hermetically sealed civilizational units,” Hodgkin explains. “To get to see that’s not really the way it is or was, and to watch writers and genres moving all around the Old World.”

“Medieval World Literature, Genres and Geographies” will consider the possible comparisons or connections between different texts — poetry, plays, travelogues, etc. — produced across the world during the period between 500 to 1400. Hodgkin plans to begin the class with three mini-units that question each of the terms from the course title: medieval, world, and literature.

When exploring the term “medieval,” Hodgkin says, the students will ask themselves, “How are we dealing with the chronology of this? What are the gains and losses in grouping together the texts of a middle period of history between ancient and early modern? Even if the category is useful for Europe where it originated, what are the gains and losses of extending it to parts of the other parts of the world?”

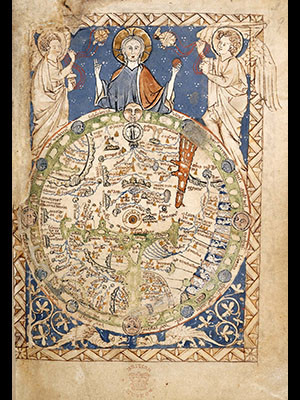

When considering the term “world,” students will consider, “In what ways is this a single cultural or literary system? Or where would we draw the bounds of that system?” Hodgkin says that they’ll think about geography partly through the lens of world-systems theory — considering how the effects of pivotal events, specifically the Mongol conquests, are similar in places that are far-flung geographically. “For example, Vietnamese and Hungarian literary calls to resistance against the Mongol conquerors,” he says. “Do we end up with similar features in different places in the system that occupy similar positions within the system?”

Finally, he says, the students will discuss what they mean by “literature” in a historical period when not every text was written down, when oral tradition was strong, and when there were high and low artistic genres written in cosmopolitan and vernacular languages.

After establishing working definitions for the three terms, the class will embark on the core work of a comparative literature course: reading two works or excerpts from different literary traditions (i.e. different genres and/or geographies, explains Hodgkin) for each seminar meeting. The class is still a semester away, so Hodgkin says the required readings are far from settled, but he can confirm for now that the following texts will be included: the Persian romance “Vis and Ramin”; the Spanish Jewish poet Yehuda ha-Levi’s imaginary interfaith debate “The Khazars”; the Tibetan “Bardo Thodol” (famous in English as the “Book of the Dead”); the “Secret History of the Mongols”; the play “The Conversion of the Harlot Thaïs” by the German canoness Hrosvitha; the epic of the Greek border lord “Digenis Akritas”; and versions from Ethiopia to Malaysia of two great medieval traveling narratives, the Alexander romance and the Buddha story (“Barlaam and Josephat”).

Hodgkin is also trying to include texts from the Americas and sub-Saharan Africa, which are difficult to capture due to a paucity of surviving manuscripts. “We will read the [Mayan mythology and history] ‘Popol Vuh’ because it’s a good example of this problem,” he says. “The earliest copies that we have of it were made post Columbian Exchange likely from oral K’iche’ sources.” He adds that he hopes this wide variety of readings will motivate students to eventually take other classes that engage more deeply with particular works or literary traditions.

Travels narratives — of migrations, pilgrimages, and even vision quests — will be a staple of the course. Hodgkin says he wants students to understand the frequent, complex mobility of peoples — artists, musicians, merchants, etc. — during the period.

“Within the space of the Mediterranean through to East Asia, it’s not just a matter of ‘this explorer moves across from here to here,’ or you know there’s this particular point of contact,” he explains. “It’s very much a single world of the verbal arts. The idea of this class is to have students think about how these forms and genres move around and all the different wonderful things that come out of that mobility.

“The genealogical linkages are in many cases impossible to trace, and in other cases at least difficult, but we can think about it as a class,” continues Hodgkin. As they encounter similarities between, for example, East Iranian Buddhist lyrics and the poetry of Tang China’s Li Bai, they will ask together: What might be a matter of emulation or influence? What is more a similarity of forms? And what is just the universality of human experience?

Much like Butterfield, Hodgkin hopes his students come away from this class with a different sense of the world. “I think we live in a moment when there are a lot of non-specialist ideas about civilizational units out there — about the clash of civilizations and the idea that differences between them are just so old that they can’t possibly be bridged.” But this isn’t true, he says. “The fluidity of those units in the pre-modern world may come as a surprise to a lot of people.”